You won’t know how to pronounce it at first. You’ll see the word with the daunting umlaut over the “o” and you’ll pronounce it donor, as in organ donor. Or maybe you’ll pronounce it like Santa’s reindeer, Donner (and Blitzen). When you finally realize how it’s pronounced it’ll all make sense.

Döner, which is undoubtedly the best street food in Berlin, is pronounced like the sound you’ll make when you eat it, as in “ooh and aww.”

Much like the cities of America, Berlin has a distinct smell. In the mornings, the smell of freshly roasted meats wafts through the streets. The street vendors are already set up and ready to go for the morning commuters. Sausages are stacked and ready and the meat spits are fat and dripping, ready to be served up to their first hungry customers.

The first time I had a döner I was on the train coming back from Dresden, about two weeks into the program. I ordered one in the train station before boarding, wrapped up in foil. When I got on the train and unwrapped it, I knew I had made a mistake. It’s a terribly messy meal.

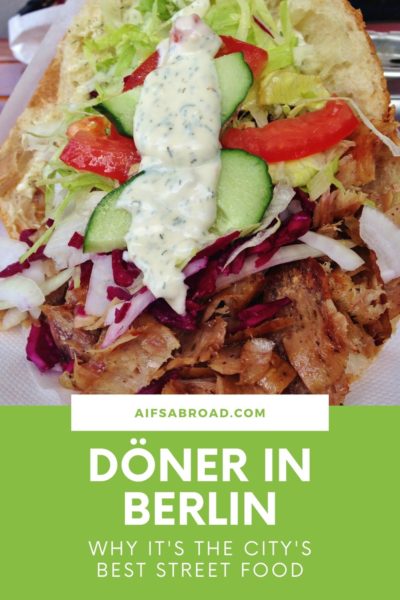

The sandwich starts with a Turkish flat bread, toasted so it’s crisp and warm. The bread is spread with your choice of sauce (my personal favorite is the garlic sauce) and then piled high with lamb shaved right off the spit, onions, cabbage, lettuce, tomato, cucumber and another dollop of sauce. If you order it to go, the vendor will smash the sandwich down for you and wrap it in foil, letting the sauce and the meat juices blend together inside the wrapper. When I opened mine the juices immediately began to drip out, and I quickly dodged them, letting them drop onto the train floor. Lettuce and cabbage followed in pursuit, and I hoped a staff member wouldn’t come by and see the mess I had made.

Then I took my first bite. The taste is almost indescribable. The closest thing we have in America is the gyro. The meat is the same and the sauce is like tzatziki but has much less of a cucumber flavor. It’s really the cabbage and the bread that make it so unique. The cabbage and the onions give a slightly sweet flavor that distinguishes it from a gyro. Gyros are also made with a softer bread, but the döner bread has a crunch to it.

I continued to spill and drip all over the train floor. When I finished, my stomach stretched out to full capacity, I cleaned up my spills and took a nap until we arrived back at the Berlin Hauptbahnhof.

I learned, on about my fifth döner, that the best time of day to eat it in Berlin is when the sun’s gone down and the street food vendors are down to the last of the day’s meat. The darkness perfectly complements the flavors. One night coming home after the subways had closed and the only way back was through navigating the bus system and the trams, a member of our group ordered a döner and brought it onto the bus. We all begged for a bite of the heavenly sandwich. As we weaved through the dark city streets we passed the döner around between the five of us until it was completely devoured. When we stepped off at our stop the vendor outside the subway station was still open, recognizing us as regulars now. Sharing the döner hadn’t been enough for some and two of the guys lingered behind and ordered their own. “Eine döner, bitte” they would each say and be handed over a large lump in foil.

I probably ate close to ten döner the month that I was in Berlin. Every time someone said “too many” they would get a glare from the rest of the group. You couldn’t eat too many, even if you had one every day, because you had only been given the opportunity to do Berlin once, or YOBO, as we would proudly shout as we stepped aside to order another.

This post was contributed by Emily Cole, who studied abroad in Summer 2015 with AIFS in Berlin, Germany.